Applying Data Science to the War on Potholes

March 15, 2016

New York City set a new record for potholes last year, and if Lou Riccio’s forecast is right, New Yorkers could be in for a bumpy ride this year, too. But it’s not all bad news. Thanks in part to Riccio’s research, New York’s pothole problem may be turning around soon.

An operations researcher at Columbia University, Riccio analyzed nearly 20 years of pothole and street-resurfacing data to figure out whether bad weather or bad management is behind the large number of potholes the city patches up each year.

His conclusion? Chronic underfunding of road repairs for nearly 20 years left city streets in poor shape and thus, prone to potholes. According to a model Riccio built, 80 percent of potholes are due to inadequate resurfacing while only 20 percent are due to harsh weather, as measured by inches of snowfall.

Based on the resurfacing gap that Mayor Bill deBlasio inherited, Riccio predicts the city could see between 250,000 to 300,000 potholes by spring’s end. That’s on par with the 1970s, he says, when the city’s financial woes caused sharp cutbacks in public services.

“A high number of potholes indicates a failure to maintain city streets,” he said. “Fixing potholes rather than preventing them is far more costly.”

Riccio’s prediction is based on a statistical analysis of the two main contributing factors for potholes: the amount of road repairs done each year and how much snow has fallen (an indicator of how harsh that winter was.) As most people have been led to believe, the number of potholes is strongly related to snowfall levels, but not nearly as much as a lack of road repairs, he says.

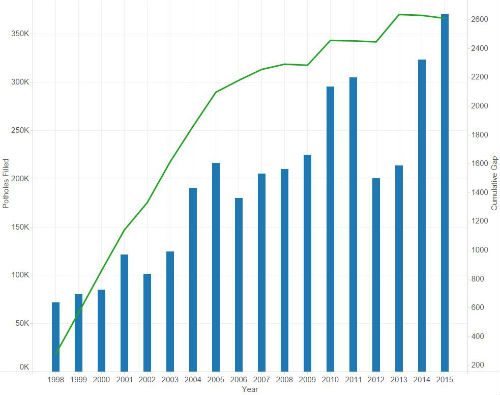

In the mid-1990s, when the city rated about 85 percent of its streets as “good,” and resurfaced about 1,500 lane-miles per year, it averaged only 70,000 to 80,000 potholes annually. When the city cut resurfacing to 600 lane-miles per year, in the mid 1990s through the early 2000s, the number of streets rated “good” fell to 70 percent, and the average number of potholes exploded, to between 200,000 and 300,000 a year, where it remains.

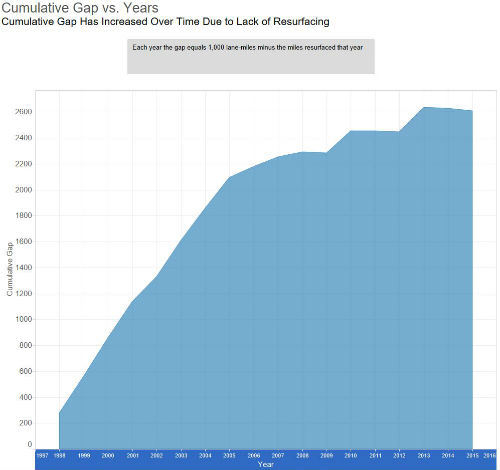

As a former NYC Department of Transportation commissioner, Riccio has calculated that the city needs to resurface at least 1,000 lane-miles, or five percent of its 20,000 lane-mile total, each year to keep pace with normal deterioration. Regular resurfacing, it turns out, wards off potholes much the same way that conscientious brushing deters cavities.

By Riccio’s count, the city currently has a 2,600 lane-mile deficit in underfunded resurfacing, a distance he compares to a one-lane road stretching from NYC to Phoenix. With no gap and no snow, the city would see less than 8,000 potholes a year, he says. Under the current gap of 2,600 lane-miles, he estimates that each lane-mile produces 84 potholes, and each inch of snow, 1,428 potholes. If 30 inches of snow fall this winter, he predicts NYC could see as many as 300,000 potholes. His findings, using data through fiscal year 2015, are similar to results published in 2014 in OR/MS Today.

Not long after the piece, Pothole Analytics, came out, Riccio sent a copy to deBlasio’s new DOT commissioner, Polly Trottenberg, hoping his analysis could justify increased spending on road repairs. It apparently did.

Last year, the DOT’s resurfacing budget increased from 1,000 lane-miles to 1,200 lane-miles, and is scheduled to grow again, to 1,300 lane-miles, this year.

With these investments, Riccio predicts a turn around in the war on potholes. “By next spring there should be a drop of between 15,000 to 35,000 potholes,” he said. “If the budget stays healthy, the city should see a comparable drop each year thereafter.”

— Kim Martineau