When a person reaches for a cup of water, thousands of muscle signals fire in coordination. For stroke survivors, that seemingly effortless act can become impossible, and even the most advanced rehabilitation techniques have yet to fully restore this functionality.

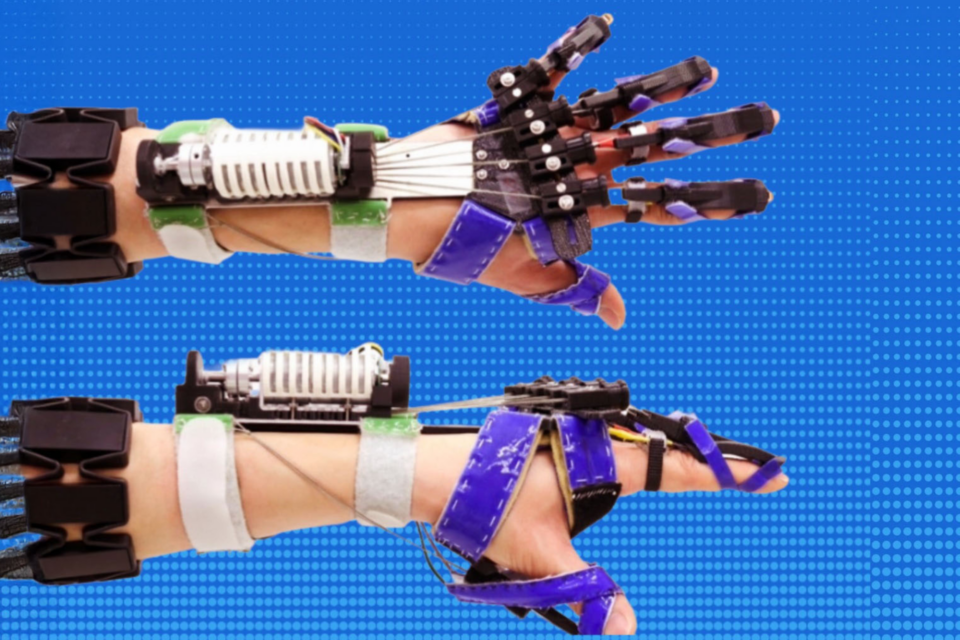

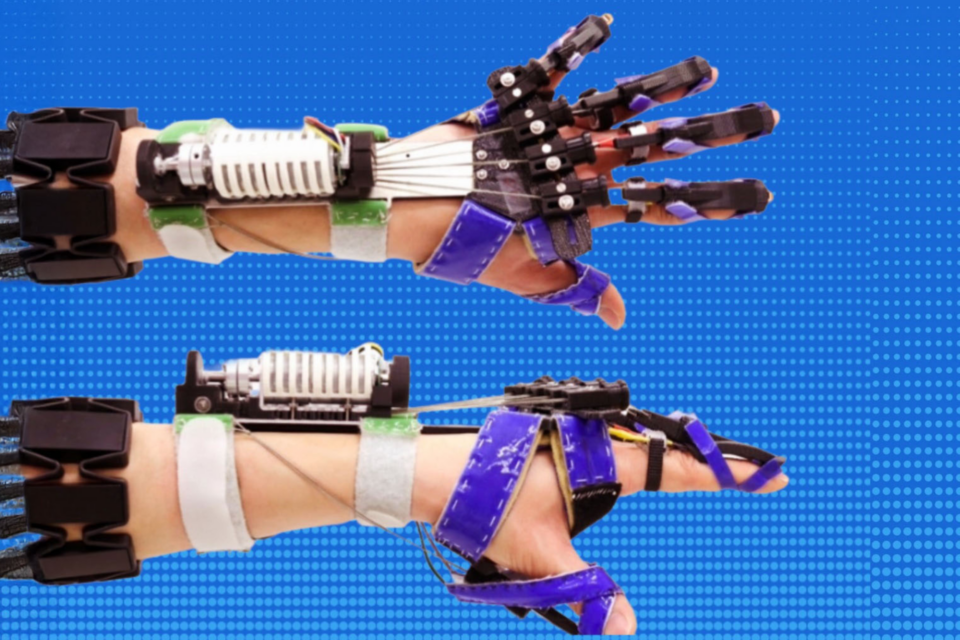

A collaboration between Joel Stein, Professor and Chair of the Department of Rehabilitation and Regenerative Medicine, and Matei Ciocarlie, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Columbia Engineering, is tackling that challenge. With support from the Data Science Institute Seed Fund, their team has built a new kind of wearable robotic device: one that interprets what its user intends to do.

The project, called ChatEMG, applies the same kind of generative machine learning used in LLMs like ChatGPT, but instead of predicting text, it interprets the patterns of electrical signals that muscles generate and translates them into movement. The collaboration was launched through a Data Science Institute Seed Grant, which supports new, interdisciplinary collaborations between Columbia faculty across disciplines.

“Rehabilitation of the hand is one of the hardest problems we face,” says Stein. “It is where the big needs are. There are millions of stroke survivors with permanent impairment, and there are no truly effective solutions. Our goal is to change that.”

Reading the Language of Muscles

Electromyography (EMG) measures the tiny electrical impulses that occur when nerves activate muscles. For Ciocarlie, a roboticist, and Stein, a neurologic rehabilitation expert, EMG provides a critical bridge between the brain’s intent and the body’s motion.

“EMG is a kind of language your muscles speak,” Ciocarlie explains. “So it makes sense that the same tools that were developed for ChatGPT can instead be applied to EMG data to interpret the user’s intended movements from muscle activity.”ChatEMG interprets signals in real time, allowing a robotic orthosis (an external assistive device worn on the hand and arm) to move as the user intends. The device doesn’t just amplify movement; it predicts what the user means to do, distinguishing intentional muscle signals from involuntary ones. To date, the system has been validated with able-bodied participants, demonstrating its ability to translate muscle activity into predicted motion — a key step toward clinical testing with stroke survivors.

While robotic devices are already able to help with walking when one is walking at a rhythmic, steady pace, creating a device that could address hand movements is a special challenge.

“Hand movements are unpredictable and highly specific,” says Stein. Even a simple act involves tremendous complexity. “Just carrying a glass of water for five seconds involves over 500 predictions,” adds Ciocarlie.

After a stroke, that complexity deepens. “The brain is no longer directing well,” Stein says. “The signal is no longer accurate. So we have to understand how the device will interact with a person’s unique impairment patterns, to help in exactly the ways they need it most.”

“Intent is at the heart of this project,” he adds. “This has been the biggest challenge—and where we are most innovative.”

How ChatEMG Learns From Scarce Patient Data

The core innovation lies in how ChatEMG learns. To assist with movement, traditional machine learning models require large, personalized datasets, difficult to obtain in clinical settings. AI allows the team to augment limited patient data with synthetic data modeled on healthy volunteers and other stroke patients.

Because the model is pre-trained on a large corpus of EMG data, it adapts quickly to new users. “In tests, we’ve had people put on the EMG armband for the first time, and the model immediately understood their muscle activity patterns and was able to infer their intent,” Ciocarlie explains.

The team completed their proof-of-concept this summer. “We’ve been collaborating on this type of work for over a decade, but this specific innovation of using generative architectures to predict intent is very new – and the seed grant allowed us to get it off the ground,” Stein says.

To the team’s knowledge, this marks the first use of a generative model trained on synthetic data for functional control of an orthosis by a stroke survivor.

The crucial element allowing this advance is collaboration. “This project only succeeds when clinicians, engineers and patients all work together from the very beginning,” Stein says. “It’s at that moment when the device is on a patient, and everyone is observing together, that the most effective collaboration emerges.”

Data Science in Motion

With their Seed Fund, the team has built and validated the generative models that underpin ChatEMG, and secured additional funding, including from Amazon and the Betty Irene Moore Foundation. Having demonstrated success with able-bodied users, they’re now moving toward clinical trials with stroke patients.

“Our work shows that intent prediction using generative architectures can dramatically improve both rehabilitation training and daily living tasks,” says Stein. “We’ve unlocked a lot of possibilities, and we’re just getting started.”

Ciocarlie envisions expanding beyond EMG to integrate multimodal data, combining signals from computer vision, motion sensors, and other physiological inputs. “The ultimate goal,” he says, “is a system that truly understands what the user wants to do, and helps them do it seamlessly.”

The team has made their code open source, inviting researchers and clinicians worldwide to build on their work. For the millions of people living with motor impairments, that openness could be transformative. And for the Data Science Institute, it’s a powerful demonstration of how data science can turn intent into action with consequences for individual lives as well as the evolving field of human–AI collaboration.